Dot-Rangoli Chapbooks of a Liberated India

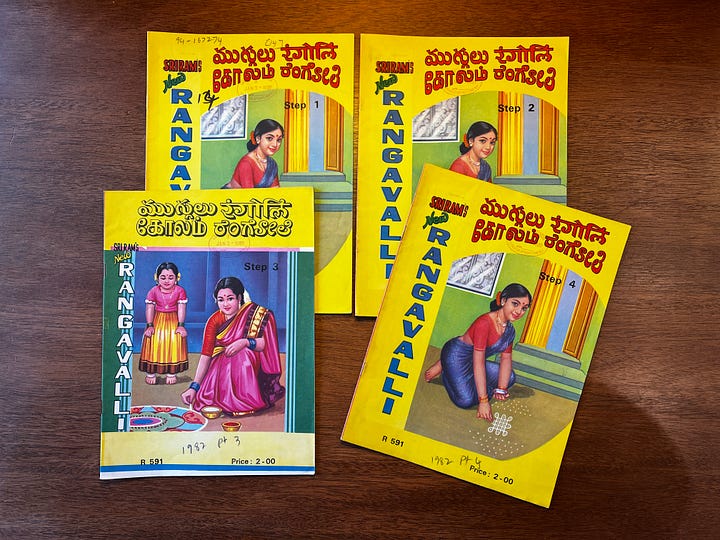

A (Graphical) examination of the Education Rangoli periodicals from the 1980s.

Part 1: Cultural Relevance and Production

The Dot-Rangoli

A cultural fixture in the Indian visual landscape, Dot-Rangoli is a communal creative practice with a rich graphic language taught through making. It is practiced on a regular basis in the southern and Western parts of India by drawing patterns outside one's house to ward off evil spirits, cleanse the front yard, and welcome the good faith of gods and guests alike to the doorstep. On a related research trip to the Library of Congress, I came across a box of Rangoli chapbooks from the 1980s—a period of cultural and national importance to Indian history.

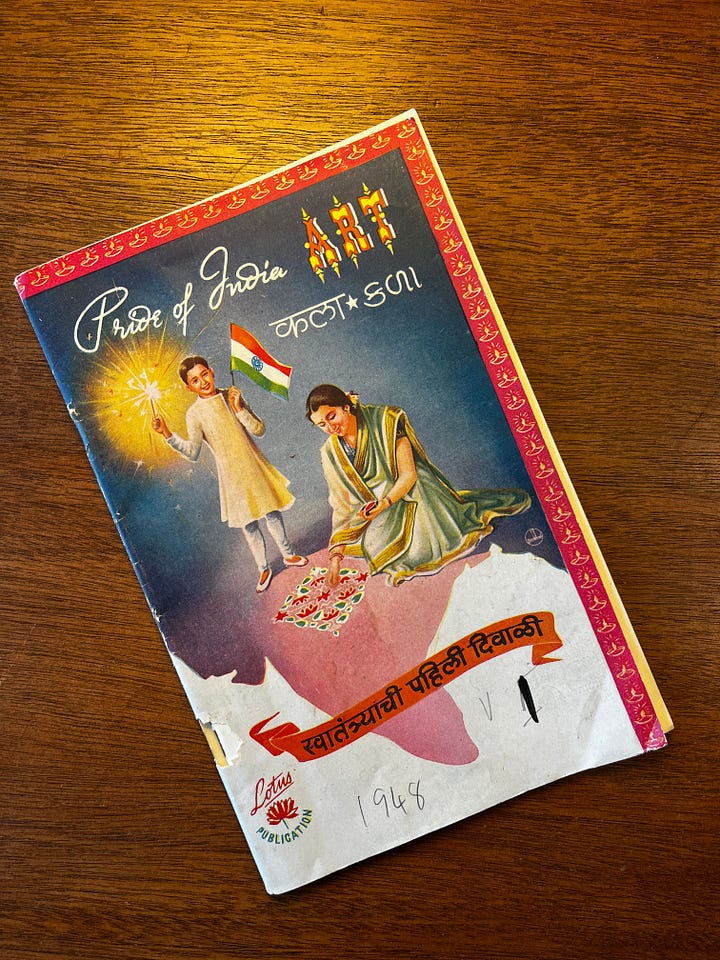

Being an independent nation for almost 30 years now, 80s was a period of political upheaval —Indira Gandhi’s assassination, etc—and cultural transformation in the country. A start of reclaiming pride in its culture, history, and people: India winning the Cricket world cup, the arrival of color television, the television adaption of Ramayan aired by Doordarshan—which grew to be one of the most popular TV shows— and the rise of alternate cinema, we began telling our own stories. In this transformative period, these Rangoli chapbooks, with their glossy pages, photographs, and illustrations of women, and ornate Rangoli drawing techniques and methods, helped define the role of an ideal wife, the significance of decorative arts in daily life, and the possibilities of independent and small-scale publishing. These chapbooks provide a valuable look at the role of graphics during a culturally transformative time, and give us a peek at the material and visual culture during this time.

The Chapbooks: Audience, Intent, and Content

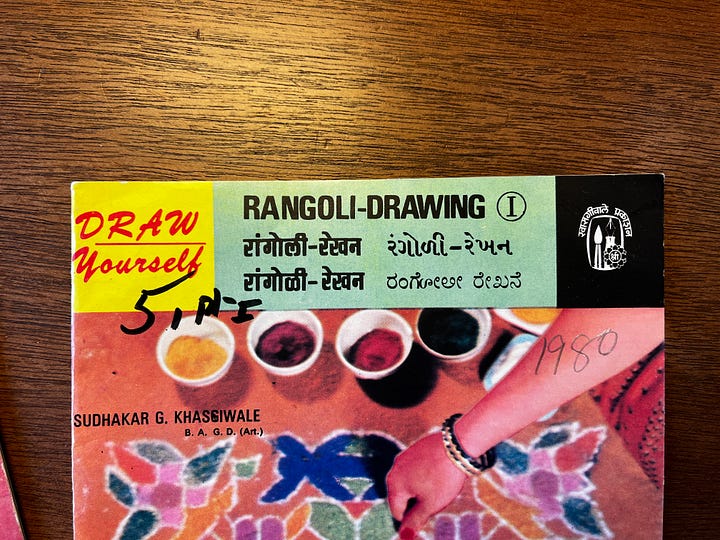

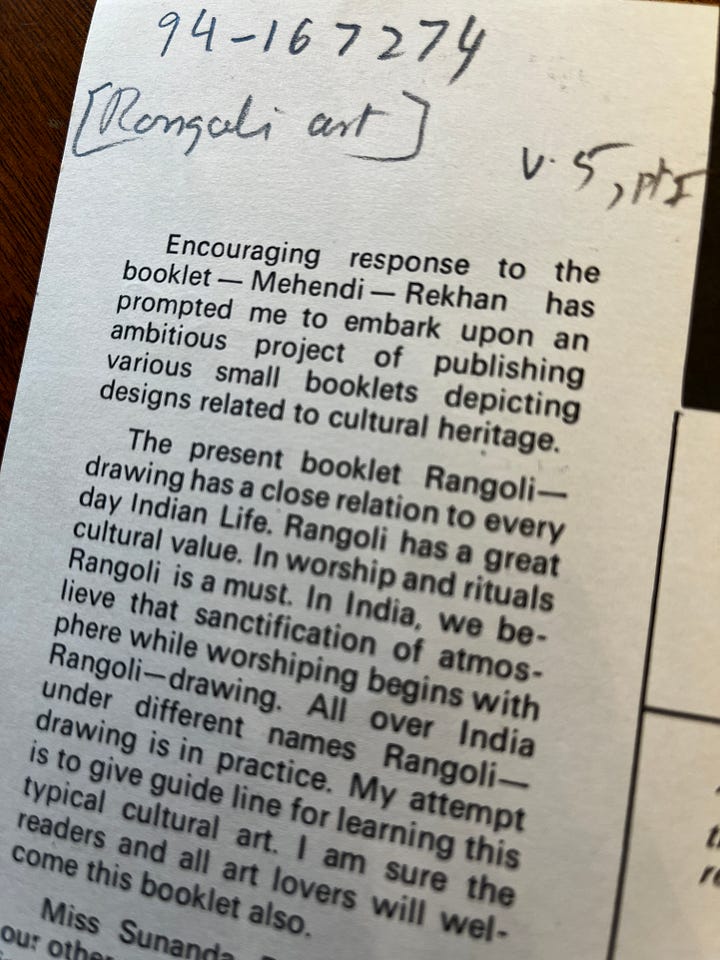

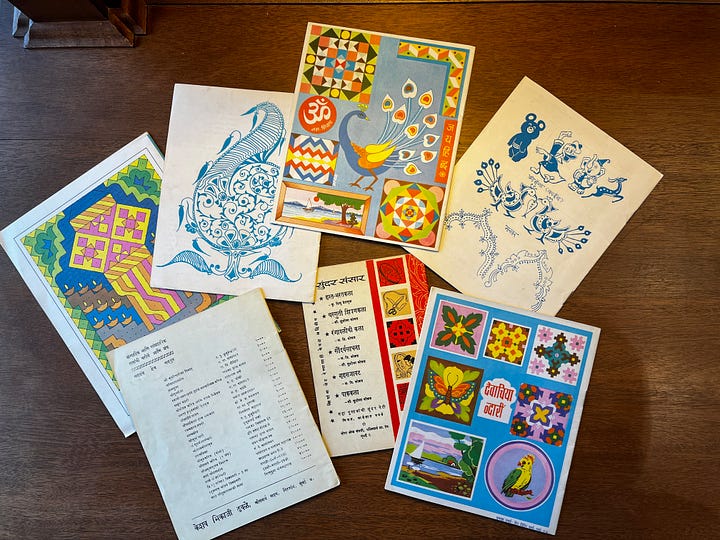

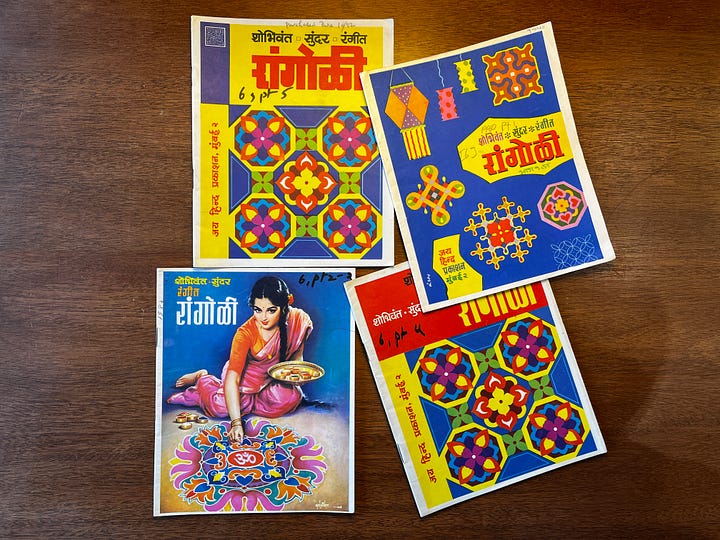

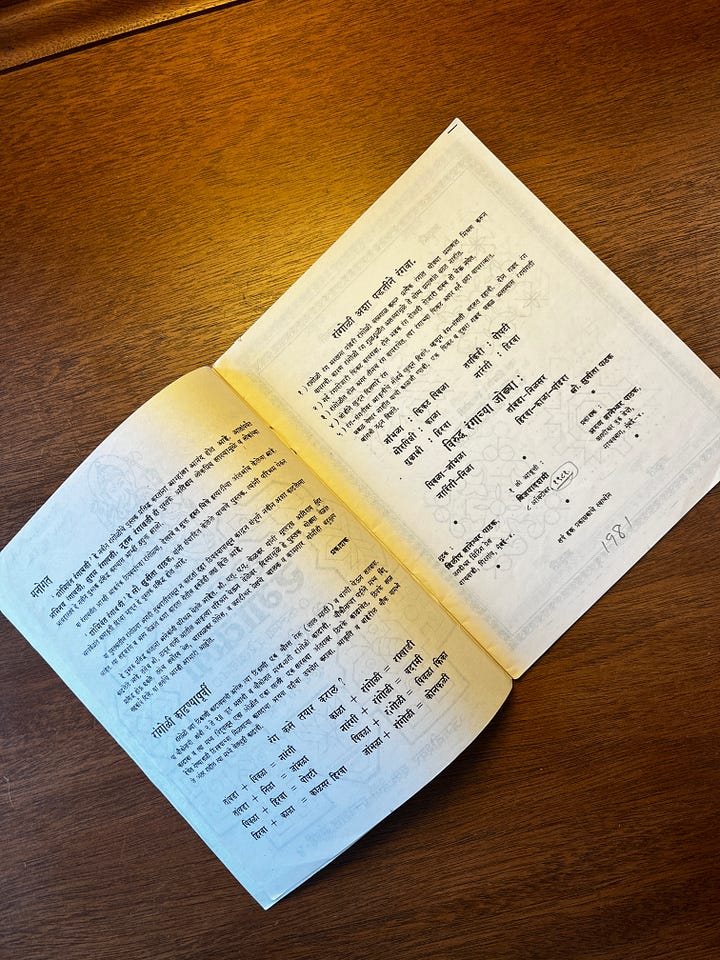

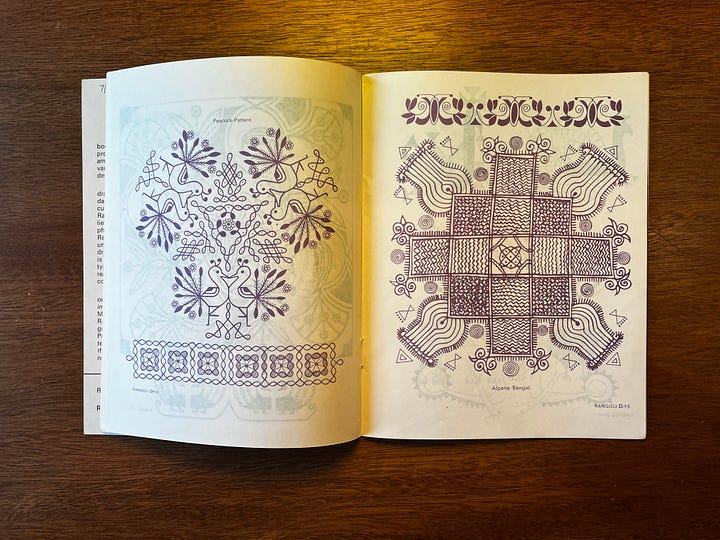

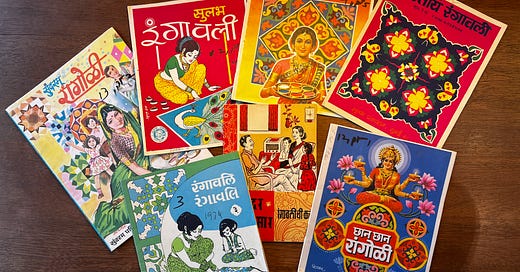

Leading educational publishers such as Navneet Publications, and growing book depots in cities were publishing these chapbooks periodically. But upon investigating author and publication names, I also suspect that many women were publishing independently, distributing through smaller bookshops. Publisher names sometimes share last names with author last names, suggesting independent publishing by the women or family ties. Almost all of the books were written by women, and for women. The author's notes in the books give us these clues about the intended audience, along with ideas of patriotism, cultural pride, and the innovative spirit that comes with the freedom to practice something that was suppressed when India was a colony. Indeed, one of the chapbooks is also titled as “Pride of India”. The books draw from existing ancestral knowledge—that is part of the pride—but don’t shy away from being experimental, inventive, and creative in their offerings. The author’s notes are fascinating because some of them also discuss the author's own ambitions to write about more Indian art forms, and their pride in having documented this age-old practice and brought it to the attention of regular households. Many books are also multilingual, featuring two to three languages and scripts at a time, reflecting the historic multicultural nature of Indian cities.

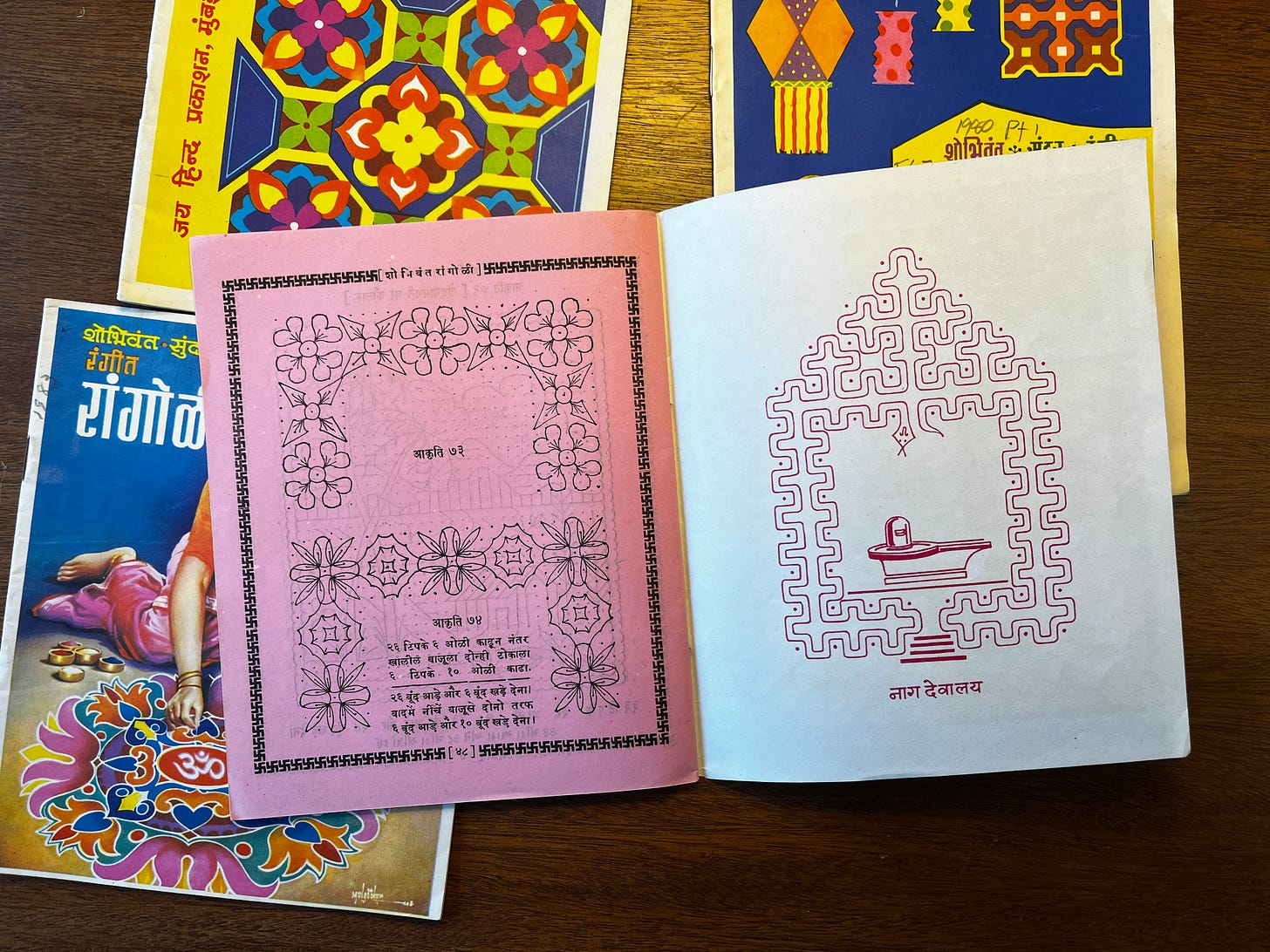

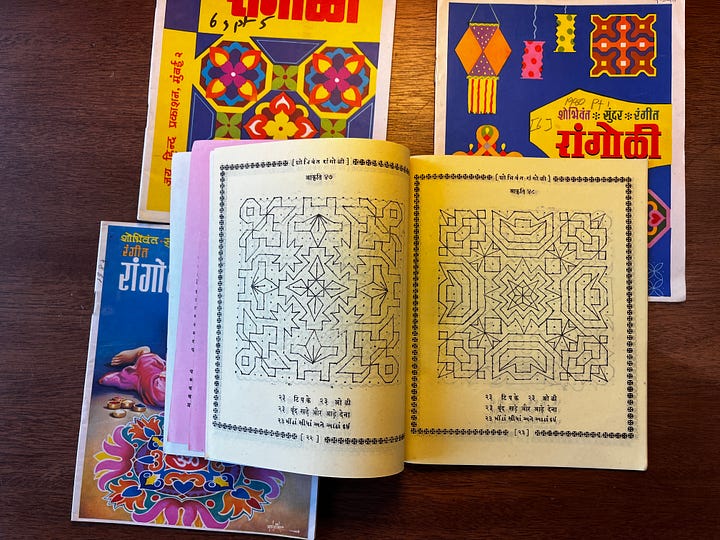

They are clearly intended to be self-help books that teach women how to create their own Dot-Rangoli patterns. The feel is very workbook-y, almost textbook-like; with newsprint paper used in the interior. But there is also a festive feeling to it, with some books using glossy paper, almost like a magazine. While most instructions are printed in black or a single, bold and bright color, many books also use colored paper with black text on it. I believe this is to imitate the colorfulness of the Rangoli itself.

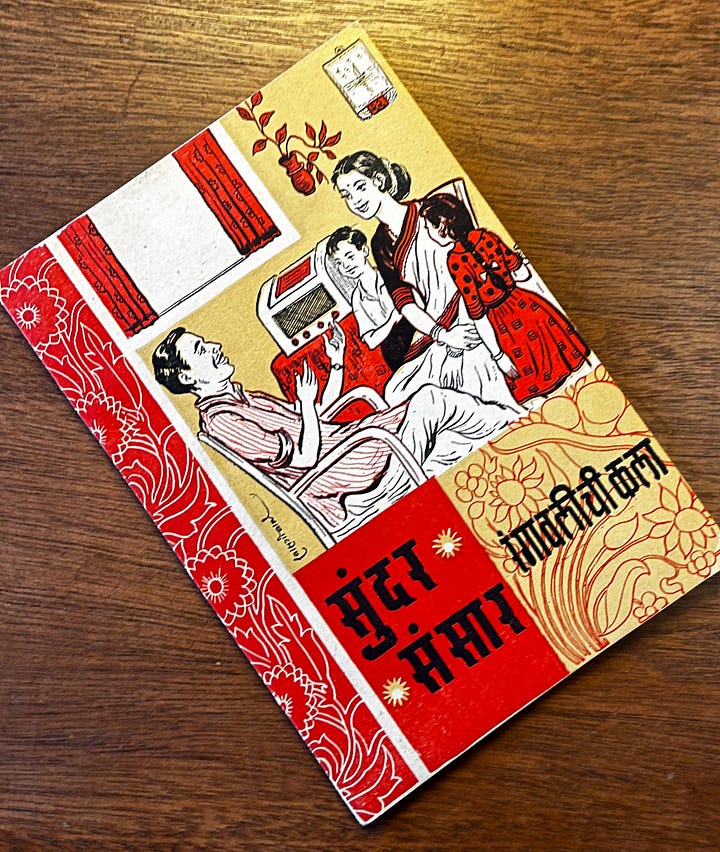

This was also a time when offset printing was on the rise and lithography was getting less popular; most books were printed on offset presses that are long gone. The production quality, disregarding the old nature of the preserved books—feels cheap and fast. Appropriate for a periodical. These were not meant to be collectibles, but rather reference materials to then grow into your own practice. The prices were not extremely cheap but pretty affordable for a middle class household. The average price per book was Rs. 2, and the more expensive ones—with glossy covers and heavier paper—cost up to Rs. 6.

Imagery and Color

From the books that I examined, 80% of them featured illustrations and photographs of women on the cover. Women wearing saaris, drawing an elaborate Rangoli, carrying the Rangoli thali, and looking very happy doing so. There were several books that also accompanied kids watching the mother draw the Rangoli, or a happy family in perfect domestic bliss: all covers showing the perfect family that draws Rangoli and stays happy together. The first spread in almost all books offers a welcome message: almost as though you were entering a living space, which is what a Rangoli does. The back covers feature equally vibrant illustrations of festival-related artifacts and completed Rangolis.. They also feature ads for other titles by the publications. Some covers also feature big beautiful completed Rangolis, decked up deities, and decorated houses ready to celebrate festivals. Common motifs include beautiful flowers and plants, birds, deities, lanterns, and other decorative objects.

Colors are inspired from the Rangoli powder colors themselves: vibrant colors, always used in complementary or split complementary color schemes. Covers are high contrast, bright, bold, and festive. With the price and nature of these chapbooks, I imagine it being a competitive market. This may explain the design decisions to make attractive covers that fight for your attention and showcase the most beautiful patterns. Interiors are comparatively mellower, owing to their purpose of teaching, with clear instructions, high contrast monochromatic or black and white pages.

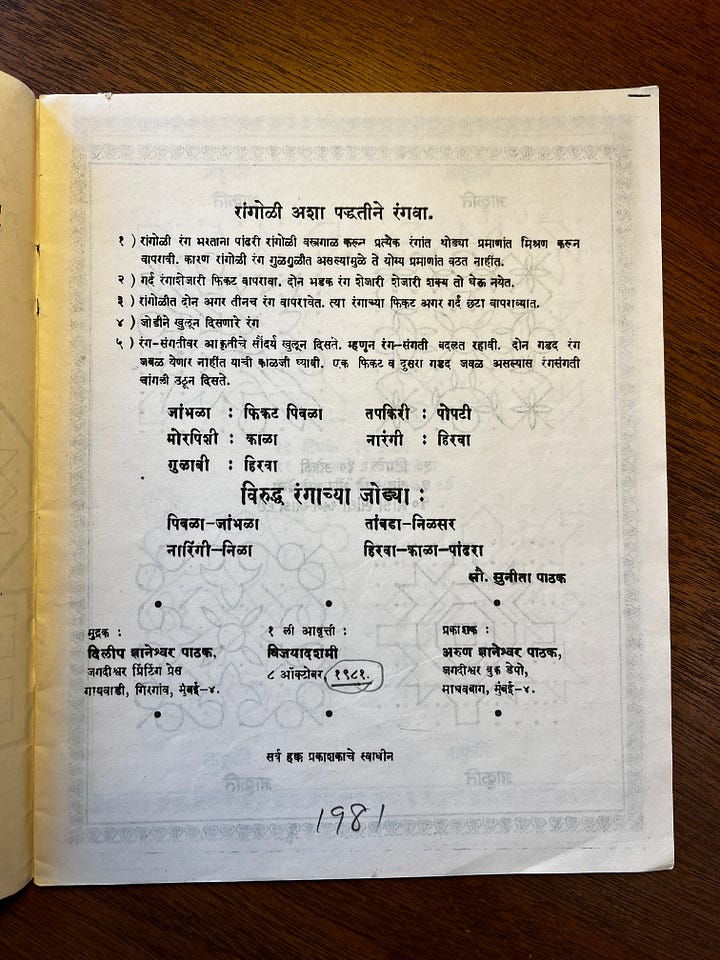

Art Education and Pedagogical models

Reading the author’s notes was my favorite part of this process. It contains the importance of Rangoli to Indian culture, their relationship to the craft, and what I took to be notes about their pedagogy. All books also illustrate techniques of the fingers and the correct ways to use wrists, because this is the basis of drawing Rangoli. The instructions are preceded with a spread explaining the logic, guidelines, and the use of color in Rangoli. These rules almost feel like instructions for a science experiment, and would be the envy of any contemporary style guide.

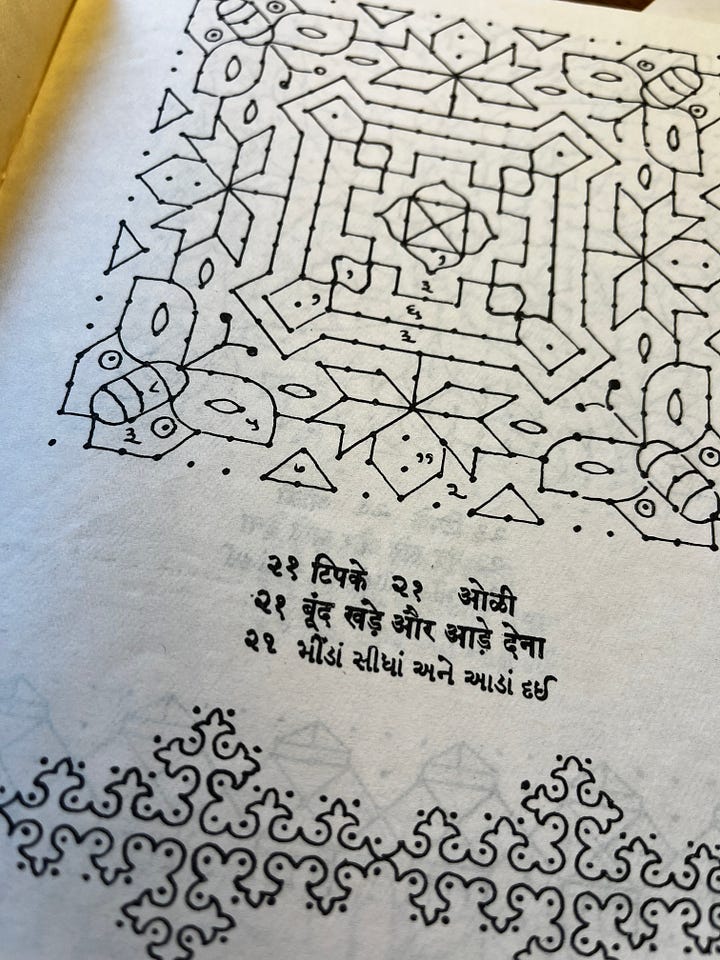

Pattern-making instructions are clear and easy to understand. They are meant for a broad audience from a beginner to a mid-level practitioner. They offer patterns that extend from being simple to becoming more complex with the addition of rows and columns of dots, providing a good balance between rules and inventing patterns. Instruction pages have the numbers of rows and columns of dots and notes on how to connect them. Since the design or pattern depends on the dot grid, Rangoli can be as small, large, complicated, or simple as the number and pattern of the dots themselves. This method simplifies even the most complex designs through the matrix of dots. While the complexity of the design depends on the complexity of the dot grid, the books illustrate the grid clearly, to break down the most complicated organic or geometric forms into simpler shapes and forms. The dot Rangoli helps you easily create complex organic and geometric forms. The guide of dots enables you to get started, the straight lines and curves help you create shapes, and the overall grid allows you to compose your pattern: and each process is broken down in the instructions. The process of making Rangoli is best learnt through making. Sometimes you figure out the designs as you make the patterns. So giving it this scientific approach may feel unintuitive to a free-hand Rangoli practitioner but can serve as an excellent starting point to understand the intricacies of this complicated mathematical craft. Rules and design always have a complex relationship and this model shows how rules are to be known before they can be broken. Instructions illustrate the modular nature of the Rangoli, demonstrating how increasing the rows and columns alters both the foundation and the overall pattern.

The one aspect that it thought was missing in these books is the Collaborative principles of co-working, process sharing, playing catch, and delegating that are all applied in making the Rangoli. Both collaborative making and breaking down the rules to its smallest element serve as an excellent pedagogical model that can be used in art and Design education in India.

Cultural impact

The availability of such affordable magazines at large definitely helped increase the popularity of the Rangoli. None of this is not copyrighted material but builds on available knowledge. Participating in and the culture surrounding Rangoli has created an educational community focused on sharing, preserving, and building upon these traditions. My grandmother used to keep a notebook filled with new and old dot patterns, along with notes and annotations, not very different from the chapbook instructions. Today, YouTube and other digital media are more common spaces for sharing and creating this knowledge. It remains accessible and widely practiced, perhaps in different capacities than before, and the chapbooks played a small role in fostering and continuing this legacy of knowledge preservation, creation, and sharing.

In Part 2, I discuss the Typography and Layout of these chapbooks.

Further Reading and References

Special thanks to Jonathan Loar, South Asian Reference Specialist at the Library of Congress.

Rooftop Blog, "A brief history of Lithography in India”.

Incredible!!

Wow! 🤩